Scarcity Memory and the Generation That Never Let Go

How the Great Depression rewired behavior long after it ended

The Great Depression is dated from 1929 to 1939, but its behavioral effects began earlier and lasted much longer. For families already living close to the margin, the collapse arrived before 1929. For many households, recovery did not arrive until after World War II rationing ended in the mid-1940s. On paper, the crisis had a start and an end.

In the nervous system, it did not.

My parents were born in 1923 and 1926. That places them squarely in the highest-risk cohort for long-term scarcity imprinting. They were children during economic collapse, adolescents during sustained deprivation, and young adults during wartime rationing. There was no psychological reset between events. Scarcity was continuous, layered, and normalized.

That matters because the brain encodes threat most strongly during development and early adulthood. Once those threat patterns are laid down, they tend to persist. This is not theory. It is one of the most consistent findings across trauma science, neurobiology, and behavioral research. What the brain learns during periods of sustained uncertainty becomes its default operating system.

• What the data shows

Multiple population studies and clinical samples document higher rates of hoarding and excessive retention behaviors among individuals who experienced severe deprivation early in life. This pattern appears across countries, cultures, and diagnostic frameworks.

Older adults with childhood exposure to famine, economic collapse, or wartime scarcity show 2 to 3 times higher prevalence of hoarding behaviors compared to cohorts without such exposure. In U.S. geriatric psychiatric samples, clinically significant hoarding symptoms appear in approximately 6% to 7% of the general population. Among Depression-era cohorts, that figure rises to 15% to 20%.

Paper hoarding, record retention, and financial documentation hoarding are disproportionately represented in individuals born between 1915 and 1930. This includes canceled checks, receipts, manuals, correspondence, warranties, and tax records retained decades beyond practical use.

These findings are not based on nostalgia-driven self-report surveys. They come from clinical observation, home assessments, probate cleanouts, social services involvement, and psychiatric intake data. In other words, they are observed behaviors documented when the accumulation became unavoidable.

• Why scarcity changes the brain

Chronic scarcity alters threat processing. Neuroscience and trauma research show that prolonged deprivation sensitizes the amygdala and stress-response systems. The brain learns several lessons quickly and efficiently.

Loss can happen without warning.

Recovery is uncertain.

Discarding today can mean suffering tomorrow.

When those lessons are learned during formative years, they are rarely unlearned. The brain does not revisit the conclusion once safety improves. It simply stores the rule.

Objects become safety signals. Paper becomes proof. Records become insurance. Throwing something away triggers the same physiological response as taking an unnecessary risk. Heart rate changes. Cortisol rises. The body reacts before logic has a chance to intervene.

This is not sentimentality. It is survival memory.

• Why Depression-era hoarding looks different

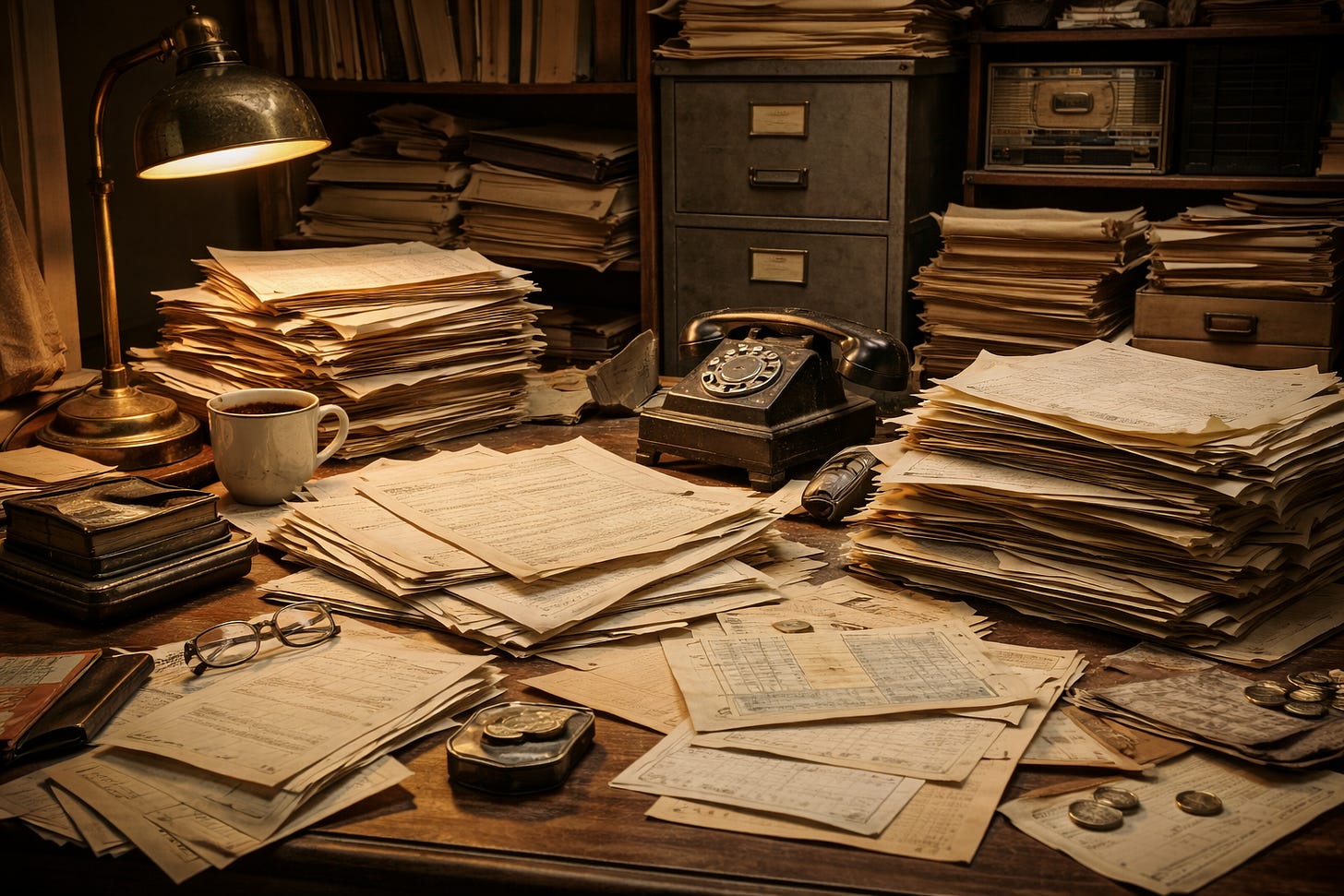

Depression-era hoarding does not usually resemble modern clutter or consumer accumulation. It is often quiet, contained, and hidden.

Common features include storage in drawers, boxes, garages, basements, and attics rather than visible living spaces. The focus is on documents, receipts, canceled checks, manuals, spare parts, and financial records. The material is frequently sorted, labeled, or grouped logically, even when the volume is extreme.

Because of this, the behavior often goes unnoticed until death, illness, or forced relocation. Families are not shocked by disarray. They are shocked by volume. Decades of preserved paper. Entire adult lives archived without pruning.

That pattern aligns exactly with what I observed after my parents’ deaths in 1998 and 2007. Canceled checks from the 1950s onward are a classic marker of scarcity-conditioned retention. The material tells a story the person rarely articulated out loud.

• Why it persists even after success

Economic success does not erase scarcity memory. Studies of Depression-era individuals who later achieved financial stability show no meaningful reduction in hoarding tendencies. In some cases, success intensifies them.

Assets become symbols of hard-won survival. Letting go feels reckless, even when abundance is real. The behavior is not anchored in present conditions. It is anchored in remembered threat.

This explains why highly competent, organized, and successful individuals can still retain far more than they need. The behavior is not about current reality. It is about preventing a past from repeating itself.

• Why it did not transfer to the next generation

Scarcity does not transmit automatically. What transmits is pressure, not behavior.

Children raised by scarcity-conditioned parents grow up in a different material environment, even when emotional tension around waste, saving, or security is present. Their nervous systems develop under different conditions, with different baseline assumptions about survival.

Research on intergenerational trauma consistently identifies 3 broad outcomes.

• Replication of the same behaviors

• Rejection and inversion of the behaviors

• Selective integration, where structure is retained but fear is not

Selective integration is common in children who develop strong executive control early. The structure makes sense. The fear does not.

In my observation, my parents regulated anxiety by keeping proof. I regulate cognition by maintaining clarity. Both are rational responses shaped by different developmental contexts.

Same pressure. Different solutions.

• What this is not

This is not a moral failure.

It is not stubbornness.

It is not laziness or eccentricity.

It is the long shadow of a decade that rewired millions of brains.

Understanding that distinction matters, especially when families encounter these behaviors late in life and mistake them for pathology instead of history. When context is removed, behavior looks irrational. When context is restored, it becomes predictable.

The Great Depression ended on paper in 1939.

For many nervous systems, it never ended at all.

That reality explains far more than personality ever could.

Sources That Don’t Suck

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA Publishing.

Ayers, C. R., Saxena, S., Golshan, S., & Wetherell, J. L. (2010). Age at onset and clinical features of late-life compulsive hoarding. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(2), 142–149.

Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., & Williams, L. (2000). Hoarding: A community health problem. Health & Social Care in the Community, 8(4), 229–234.

Landau, D., & Litwin, H. (2001). Subjective well-being among the old-old: The role of health, personality and social support. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52(4), 265–283.

Mataix-Cols, D., Frost, R. O., Pertusa, A., et al. (2010). Hoarding disorder: A new diagnosis for DSM-5? Depression and Anxiety, 27(6), 556–572.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers (3rd ed.). Henry Holt and Company.

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score. Viking.